A big chess tournament is a glorious homage to nerdy excellence and drab fashion. The tournament Milo and I attended in January, although largely overshadowed by our adventure with Lucky the Lorikeet (read here), delivered magnificently on both counts.

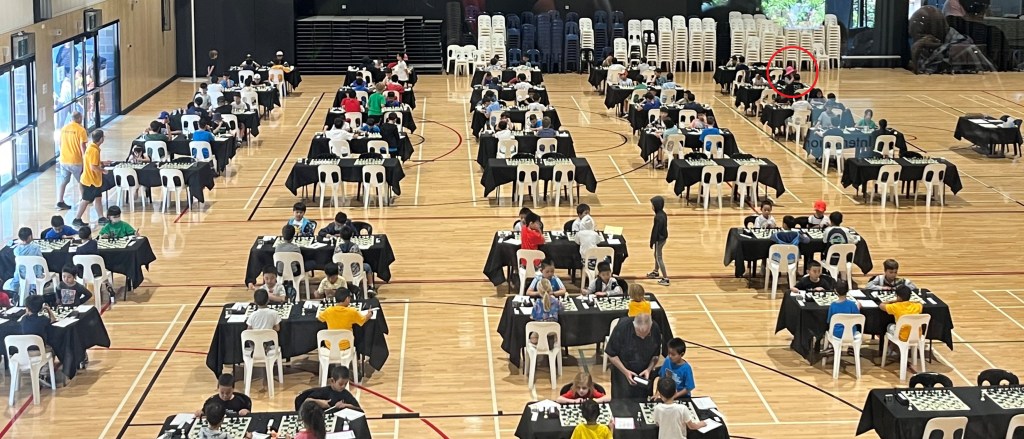

A tournament of this size requires a big venue; a school hall, basketball stadium, something of that nature. The folding trellis tables are laid out in rows and rows, each with its own chess timer and board. Adjacent each of these tables can be found a pair of children, each with a neat haircut, oversized dark coloured or grey t-shirt (Adidas or ‘chess themed’), plain shorts or long trousers in quick-dry material, white socks at medium ankle length (not high or low) and white sneakers (Adidas or New Balance). There is an occasional baseball cap in navy, white or bottle green.

Given the tournament includes 100 or more players, each participant will only play a small proportion of the possible opponents. To keep things fair, and to confidently identify a true winner, the pairings are constantly evaluated based on their last result. So, if a player wins they will move ‘up’ a table and if they lose they will move ‘down’. The top 3 or 4 players are usually pretty stagnant and consistent. These players will set up their residency on tables 1, 2 and 3 – personalising their spaces with framed pictures of their mothers, Magnus Carlsen bobble-head dolls and packets of supermarket-bought jam-filled sponge cakes. For everybody else there is quite some variability; a win rocketing you up 10 tables or so, and a loss doing the same in reverse. There are lots of intricate, tournament-specific, rules which I won’t trouble you with (mostly because I don’t understand them all), but players need to keep track of each move via a baffling, coded shorthand, written in hard copy on a score sheet. This becomes the permanent record of the game, and the outcome.

Parents and other spectators cannot be within earshot of the games and are therefore generally separated by a pane of glass, or an invisible barrier of societal judgement, or both. The parental behaviour is generally highly cordial and supportive, but also quite odd. The weirdest among that cohort stand and watch every move, sometimes pressing their faces up against the glass and then leaving little steamy halos of chess expectation behind when they step back. Despite my pre-tournament predictions and hopes to the contrary, I found myself in this cohort.

Match 1

The preamble to Milo’s first game is already well documented. With lorikeets on his mind instead of gambits named for obscure Eastern European villages, he was no match for a pint-sized, baseball capped ball of chess fury. Even from 30 metres away I could feel the intensity. Milo would think awhile about his move, make it, stop his timer, and before he had even written down his aforementioned baffling, coded shorthand, the counter-move was already made. The moves were made forcefully; there was no placing, only ploughing, and whenever one of Milo’s pieces fell, I felt genuine remorse for it. It looked painful.

Milo was unfussed about the loss and his only non-lorikeet related comment post-match was that the other chap refused to talk to him. What a pro.

Match 2

Milo slipped down a table or two and thus came face-to-face with an entirely different profile of opponent. This fellow did have a chess-pun themed t-shirt (‘Knight to meet you’ with a picture of a Knight taking a pawn, or similar) but he bucked the fashion trend with a yellow bucket hat. I liked it. Even from my distant, elevated vantage point I could tell he was chatty, and fidgety. He stood up, he sat down, he tried to engage the table to his right, he tried to engage the table to his left, and at one point he had clearly lost his scoring sheet. How he managed this on an empty one square metre table I cannot tell you.

The game ended reasonably quickly and I could tell by the smile on the face of my returning son that he had enjoyed a victory. Unlike round one, Milo had a full report for me; he had told his opponent about Lucky the Lorikeet. His opponent had then tried to tell the amazing story to the adjacent tables, and had been shooshed. He had also employed an interesting mind-game on multiple occasions during the match, saying to Milo “I bet you don’t know what I am thinking.” Milo had ignored him two or three times but then had eventually said “No, I don’t know what you are thinking!” to which his opponent had quizzically responded “Wait, I don’t know what you are thinking either!”

It all seemed like a curious, but not unpleasant interaction.

Match 3

Milo was emotionally and physically drained by the time round three arrived on the afternoon of day one. We had walked the streets looking for a vet, scoured the internet for information on Lorikeet Paralysis Syndrome and carefully drafted our email to the University of Sydney Professor. And he had already played more than two and half hours of chess.

Milo’s final opponent for the day was tiny, even among a cohort of nine-year-old chess players who are not renowned for their bulk. He sat at the edge of his chair and still his feet dangled. His chess-themed tshirt swam on him, and he looked like his little head might become irretrievably lost in his baseball cap at any moment. But in junior chess, perhaps above all other pursuits with the possible exception of professional hide-and-seek, a slight frame is no impediment to glory.

This was Milo’s longest game of the tournament. His tiny opponent seemed completely still throughout, or perhaps his clothing was so loose that the movement of his limbs had no bearing on the fabric. Milo became distracted and occasionally smiled and waved up at me. Although very sweet and heartwarming, this is rarely a recipe for victory in a game as concentration-dependent as chess. It seems unlikely that Garry Kasparov ever waved to his mum… although a quick google of ‘Kasparov’s mum’ yields a number of articles suggesting they were quite close. So, perhaps he did.

Anyway, because the game was so protracted, I started to study the parents around me, the vast majority clearly chess enthusiasts themselves (t-shirts emblazoned with slogans like “Rook You!” alongside a Rook dramatically knocking over a Bishop tipped me off). Several of them were in fact zooming their camera phones so tight that they could photograph the boards of their playing children, allowing them to analyse the moves. This analysis then precipitated mutters of satisfaction or sighs of despair, or both, but also light-hearted conversation between these parents, many of whom seemed to know each other already.

I stood quietly by myself, and once the match had come to an end, walked down the stairs to give Milo a little cuddle. It was clear he had lost and so I didn’t even ask him about it. We did a quick circle of the surrounding bushland to spot any other distressed birds and then walked together back to our hotel after an extremely eventful day.

Match 4

Readers of this blog will know that Milo doesn’t really fit the oversized grey tshirt, athletic trousers and New Balance sneakers mould. On day one of the tournament Milo had been rather demure in his attire; chess tournament tshirt and black tights (although he did wear bright red crocs with rainbow coloured fluffy jibbitz exploding out all over the place). On day two he felt a little more comfortable with the environment and so leaned in a little more to his instincts. We have an expression in our house which we use often… ‘weird is interesting’, and everybody is encouraged to be weird in whatever way brings them joy. It is a philosophy very much open to individual interpretation and on that day Milo interpreted it as leopard tights, Tournament of the Minds tshirt, red crocs and his signature giant pink floppy hat. I expected him to remove the hat once play began, but he did not, which made him very easy to spot, and probably somewhat distracting to play.

The match was short and sharp and I could tell from his bouncy exit from the gym that he had won. A great start to the day.

Match 5

Match 5 was also reasonably short, but with a less victorious outcome. The pink hat came bobbing out of the gym once again, but this time in a more languid, dragging manner suggesting disappointment or calf injury.

When we arrived together at the meeting point Milo had a wry smile on his face, which seemed a little paler than usual. “That guy was like the Terminator” he said “I knew I was going to lose as soon as I saw him. It was a scary game.” (for those movie censors at home Milo knows of The Terminator but has not seen The Terminator – at least none of the good ones). According to Milo the Chess Terminator had only spoken twice; once to tell Milo to be quiet, and a second time to tell Milo to be quiet and also to confirm it is a tournament rule to be quiet.

Match 6

The final opponent for day two wore a COVID mask and a flannie, so he too was breaking with the general norms of attire. There was no point me zooming my camera in tight to analyse the game; I would have learned nothing. However, even from my distance I could tell it was an animated game. The two of them were chatting and pointing and thrusting their hands up to ask the adjudicators questions from time to time. Both boys looked focused and alert and the game stretched beyond the hour mark again. Really quite remarkable for nine year old boys who had already played 5 intense games of chess in two days.

Eventually the match ended and Milo bounded out victorious, a stream of words and phrases and energy bubbling out of him “so my rook broke free, but then I was stuck on the back rank, but then we did an exchange to my advantage, then I spotted a winning solution, I checked with my Bishop, he blocked with two Bishops… daddy? daddy? are you listening? Then I saw I could pin him and then I did a back rank check mate.” Awesome.

We went out for burgers and ice cream spiders.

Day 3

George Flopsy joined us for the final day of play. George is a pretty awesome little dude, a stuffed monkey with long arms that hold together with velcro; so he can cling onto the handrail on a bus, or the back of a schoolbag, or around your neck.

Milo wore George around his neck all day, positioned such that he was staring directly, unblinking, at each of his last three opponents. Milo also wore his giant pink hat, so by day three had completely leaned into his weird. We checked the rule book but found nothing precluding the wearing of inanimate, long-armed monkeys around one’s neck, and the adjudicators let it slide.

As I reported in the Lucky story, Milo lost his first game of day three but then, buoyed by the wonderful news of Lucky’s survival, managed to win his last two to finish 5-4 for the tournament, and about 25th out of 100 pretty intense little chess people.

Shortly before being check-mated, Milo’s last opponent for the tournament asked him;

“Why do you have a monkey around your neck?”

“Because he’s cute and I like him.” Milo replied.

The boy nodded and agreed “Yeah, he is pretty cute.”

Check mate.

Spot the pink hat